I got invited into Airtable’s Superagent beta, and my first idea was simple: use it to help build a presentation I was already preparing for. The request was constrained (short, structured, meant to be presented) and in a domain where accuracy and framing matter—so it felt like a good test of whether Superagent could help with real work, not just brainstorming.

Afterwards, the Superagent team reached out and invited feedback. He couldn’t join the call in the end, but I spoke with his product manager. It was useful—I could share what worked, where things broke down for me, and a few broader questions about bias, alignment, and trust (beyond whatever guardrails exist in the underlying third‑party models).

Here are the takeaways:

1) Autonomy by default can slide into cognitive offloading

Superagent was helpful at the start. It generated structure quickly and surfaced a couple angles and graphic designs I might not have considered on my own. Autonomy-by-default may be genuinely useful when you want to offload early drafting. The issue for me was shifting from ‘generate a draft’ to ‘collaborate on refinements.’ I struggled to generate something I could confidently present. Superagent repeatedly defaulted to a pitch-style, narrative deck. Once the system committed to a mode, it was hard to steer, and without an editable output (or something like tracked changes/diffs), I spent more time trying to refine my initial prompt than iterating.

I ultimately ended up running Superagent Slides as seven separate tasks (each one taking about 5 minutes to complete) as I improved my prompt. Trying to refine the deck within the same task didn’t work. Each refinement took another 5-10 minutes and it often felt like the output rolled back toward the system’s defaults rather prioritizing my preferences.

The biggest barrier to using Superagent for collaboration was simpler: the final deck didn’t come out in an editable format, and I couldn’t export output in Google Doc or Powerpoint to make edits. Without being able to make normal edits, it was essentially unusable for my presentation workflow.

Net result: I spent more time waiting for and then reacting to output than thinking with the tool. That may be fine for users who want a more autonomous generator, but I was expecting the AI to act as a partner.

What I suggested to the product manager was is a more collaborative approach—closer to how code-editing tools handle changes: show proposed edits clearly (tracked changes / Git-style diffs), let me accept or reject selectively, and let each round build on what’s already working.

2) A few basics also got in the way

Even setting content aside, a few practical issues made the output harder to use:

- inconsistent hierarchy and styling across slides

- text density/sizing that wasn’t presentation-safe or accessible

These are solvable, and may simply reflect where the product is in its maturity curve. But they matter because they determine whether you can use what it generates under deadline.

3) As tools get more autonomous, trust and safety become basic product quality

We also talked about bias and reliability in higher-risk domains. I shared IFIT research suggesting models perform better in conflict contexts when prompted to do basic “sanity checks”: ask clarifying questions, surface contingencies and trade-offs, disclose risks, and take sequencing seriously.

One thing I left unsure about is how Superagent is approaching bias/alignment/trust & safety at the product layer (beyond whatever guardrails exist in underlying models). If it’s on the roadmap, I’d love to see how they’re thinking about it—this is the kind of capability that’s easier to build in early.

Final thoughts

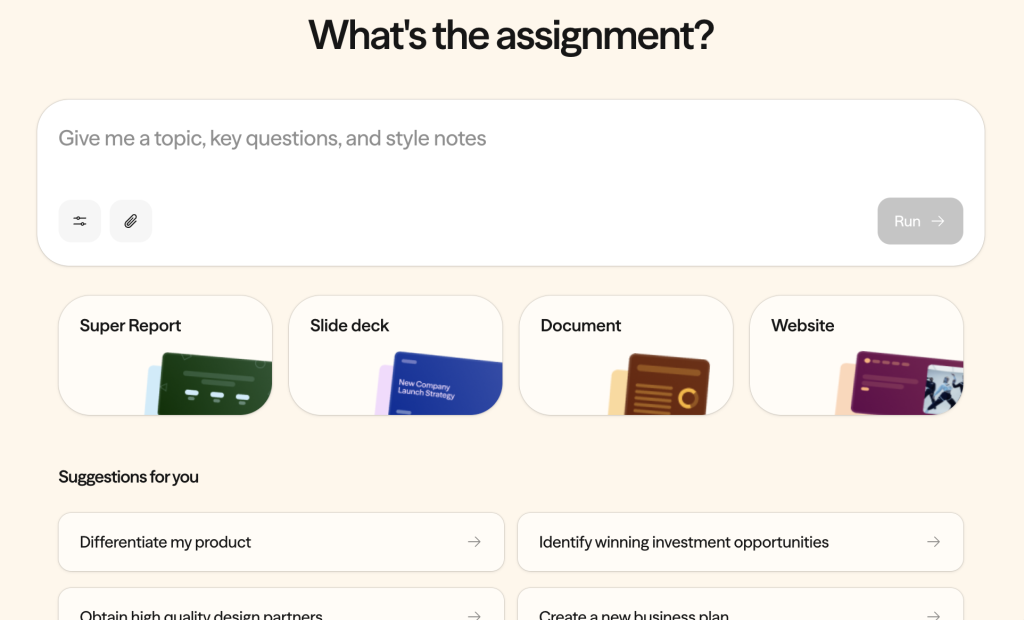

The product manager encouraged me to try Super Report, which she said is more developed. I plan to—partly because reports may naturally be easier to revise than slides.

She also said making presentations editable is already a roadmap priority, which is an important step toward making the workflow feel more collaborative.

If I zoom out, the part that stuck with me is how often AI products still treat cognitive offloading, model bias, and accessibility as secondary concerns. Those three things aren’t edge cases; they’re the difference between something that’s impressive in a pitch deck and something that’s safe and usable in the real world.