This spring, I had the opportunity to support several student-led civic tech projects through the University of Maryland’s iConsultancy program. The partnership was originally facilitated through my role at the National Democratic Institute (NDI), but when NDI’s participation was disrupted by a sweeping freeze on U.S. foreign assistance programs, I continued advising the students in a personal capacity.

What started as a straightforward mentorship experience became a much more fluid—and in some ways more meaningful—engagement, shaped by shifting roles, student initiative, and a shared interest in public-interest technology. In many ways, it reminded me of the spirit of open source: people stepping in, adapting to change, and contributing however they can. NDI itself has long embraced open source platforms like Decidim and CiviCRM as part of its commitment to digital democracy—tools that reflect the values of transparency, adaptability, and shared ownership.

Three Projects, Three Distinct Challenges

Each iConsultancy team focused on a different scope of work—specifically related to Decidim, an open-source platform for democratic participation, and a new tool that NDI was designing to make information more accessible to people with intellectual disabilities. These projects were all rooted in the open source ethos: building in the open, iterating in real time, and aiming for impact beyond the immediate team.

1. Decidim Alternate Deployment Methods

This team explored ways to simplify and modernize how Decidim is deployed across different environments. The official Heroku option had become outdated, and the manual installation process was prohibitively complex for non-expert users.

The students conducted a technical evaluation of Docker and Heroku deployment methods, tested them across operating systems, and ultimately created an updated Docker configuration tailored for production environments. Their contributions were submitted to the Decidim GitHub repo. These additions make it significantly easier to deploy Decidim in a production environment using Docker Compose. Like many open source contributions, their work advanced on community-maintained tools, with the potential to be picked up and improved by others.

2. Easy Read Generator UX Redesign

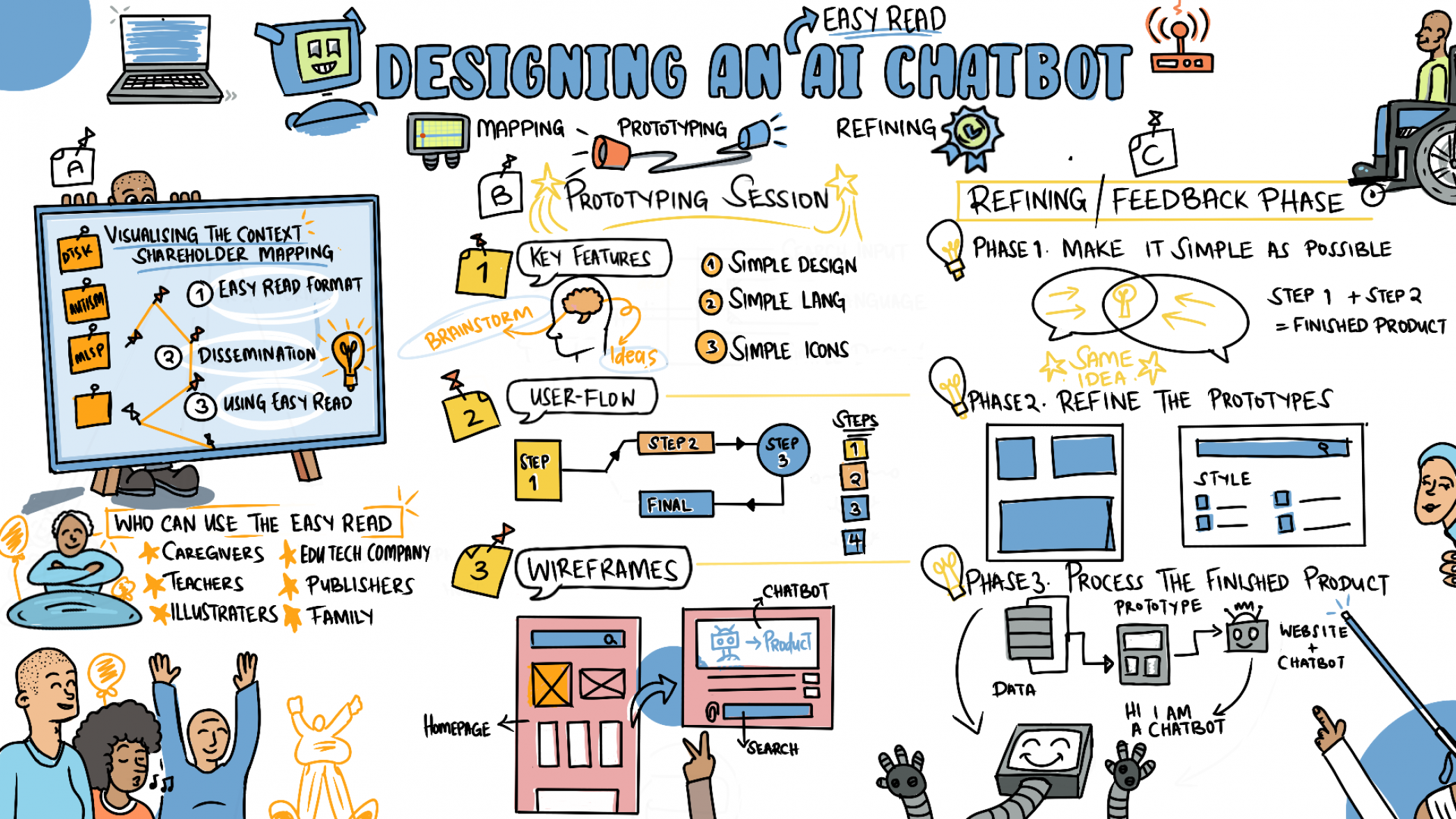

The second team focused on redesigning the user interface for NDI’s Easy Read Generator project, a tool that simplifies complex civic documents to make them more accessible for individuals with intellectual disabilities and those with lower literacy levels.

Drawing on user research, accessibility guidelines (like WCAG), and competitive analysis, the students developed a high-fidelity prototype and detailed UX recommendations. While I had envisioned an iterative redesign of existing wireframes, the team pushed the concept further—exploring new features such as login options and donation functionality. Their willingness to experiment expanded the conversation about what this tool could become.

3. Manual Installation Documentation Enhancements

The third project aimed to unify and improve Decidim’s manual installation documentation. English-language instructions were incomplete, and more robust Spanish-language documentation had yet to be translated or standardized.

The team was tasked with consolidating and testing these disparate guides, streamlining the process for deploying Decidim with all its intended features. Documentation is the connective tissue of any open source ecosystem, and while this team faced challenges in delivering their final product, the importance of the task—and the gaps it sought to fill—remains clear.

Lessons from the Field

Each project reflected the realities of open collaboration: sometimes productive, sometimes messy, always instructive. The teams that stayed organized and engaged produced genuinely useful outputs that could be built upon by others. In other cases, student groups struggled to balance their workload or needed more support to stay aligned with the project’s goals.

To be clear, this isn’t a critique of the iConsultancy model—student-led learning is, by design, exploratory. But like any open source initiative, success is rarely the result of individual effort alone. It depends on a thoughtful mix of initiative, shared norms, and an ecosystem of support. Civic tech projects, especially those aiming for real-world relevance, demand a working knowledge of community context, accessibility, and technical infrastructure—all challenging to fully absorb in a single semester. And just as open source contributors rely on documentation, mentors, and community to navigate complex codebases, student teams benefit from structured feedback, clear goals, and a culture that rewards asking questions. Those ingredients can turn short-term projects into lasting contributions.

Why I Stayed

Even after my layoff from NDI, I chose to remain involved because my commitment to the projects didn’t depend on a formal title. The UMD students brought real energy and fresh ideas. And continuing to mentor them gave me a sense of continuity and purpose at a time when many other structures were unraveling.

In civic tech, we often talk about resilience, distributed leadership, and decentralization. These principles are foundational to the open source ecosystem, where no single person or entity controls the project and leadership often emerges organically from contributors. This experience reminded me that these values aren’t just theoretical—they show up in how we navigate change. Open source projects are a fitting metaphor: they can survive the loss of their initial stewards, thriving as new contributors pick up the thread. Our work, too, can have a life beyond any single job or institution. Even when a formal role ends, the ideas, tools, and momentum we create can continue evolving—adapted, expanded, and reimagined by others who care.

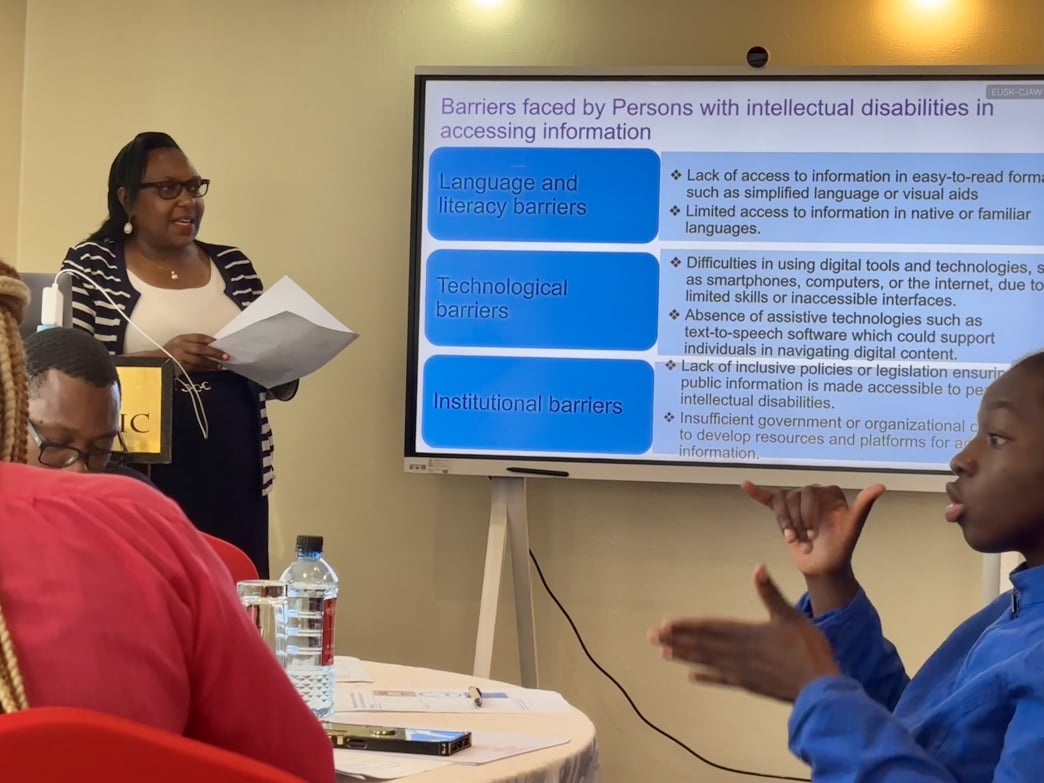

Twenty representatives from various disabled people’s organizations (DPOs) and other civic groups contributed their diverse perspectives and expertise to advance information accessibility in Kenya. These groups included the United Disabled Persons of Kenya (UDPK), the Kenya Association of the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH), Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet), Differently Talented Society of Kenya (DTSK), Black Albinism (BI), Ubongo Kids, Down Syndrome Society of Kenya (DSSK), Kenya Sign Language Interpreters Association (KSLIA), the Kenya National Association of the Deaf (KNAD), and the Directorate of Social Development under the Ministry of Labour and Social Services. The event fostered collaboration and laid the foundation for further development of accessible digital tools in the country.

Twenty representatives from various disabled people’s organizations (DPOs) and other civic groups contributed their diverse perspectives and expertise to advance information accessibility in Kenya. These groups included the United Disabled Persons of Kenya (UDPK), the Kenya Association of the Intellectually Handicapped (KAIH), Kenya ICT Action Network (KICTANet), Differently Talented Society of Kenya (DTSK), Black Albinism (BI), Ubongo Kids, Down Syndrome Society of Kenya (DSSK), Kenya Sign Language Interpreters Association (KSLIA), the Kenya National Association of the Deaf (KNAD), and the Directorate of Social Development under the Ministry of Labour and Social Services. The event fostered collaboration and laid the foundation for further development of accessible digital tools in the country.